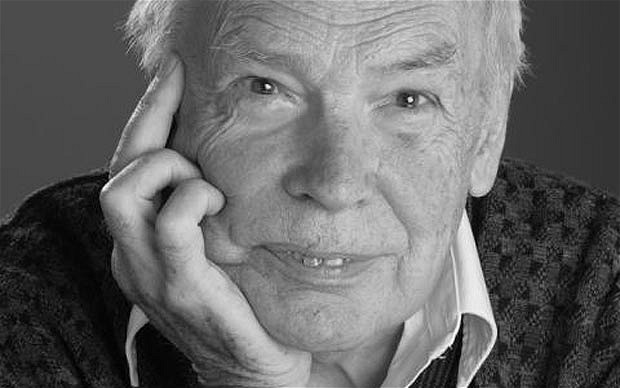

In 1976, a description of ‘Alcohol Dependence Syndrome’ appeared in the British Medical Journal (BMJ). A new concept at the time, it would go on to redefine our understanding of addiction and it’s treatment. The author of the article, the late Griffith Edwards, became one of the most significant figures in the last half-Century in addiction research. In honor of this extraordinary man, a special Supplementary Issue of Addiction has been dedicated to the career of Griffith, and his enormous contribution to the addictions field.

Griffith trained as a psychiatrist at the Institute of Psychiatry in the early 60’s, where he developed his interest for the addictions, and, would later go on to found the National Addiction Centre (NAC, formerly known as the Addiction Research Unit) in 1967. It was through the NAC he realised his vision of adopting a multi-disciplinary approach to the issue of addiction, bringing together a team of psychiatrists, psychologists, sociologists and statisticians, to reshape traditional conceptions of addiction care. It was Griffith who championed the idea of outpatient treatment and went on set up community drug and alcohol services.

‘His gift was to weave ideas taken from these various professional strands into a coherent tapestry of work that will outlive him…” Dr Jane Marshall.

Griffith published over 190 scientific papers and 40 books, most notably “Alcohol: The Ambiguous Molecule” (2000) (also known as “Alcohol: The World’s Favourite Drug”) and “Matters of Substance” (2004). Griffith designed the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) drug and alcohol policies, and contributed to the addiction sections of ICD-10 and DSM-IV. He was Editor of the SSA’s Journal, Addiction, between 1978 and 2005. Griffith was appointed a CBE in 1987 for his services to social science and medicine.

The Supplement of Addiction is developed from presentations made at a conference held at the Institute of Psychiatry, organised both to pay tribute to Griffith, and to reflect on the issues he cared deeply about: addiction science, clinical practice and public policy. It contains personal reflections by 12 scientists and clinicians who worked with and admired Griffith, and discusses the many scientific advances he was involved in.

Whilst a renowned researcher, Griffith was equally a sensitive clinician who cared greatly for his patients, a thread which runs through the various personal accounts given in the Supplement. As Dr Jane Marshall writes:

“A clinician of great humanity, he was an astute observer of alcohol-dependent individuals and would listen carefully to their stories week after week at his ward round….”

Ahead of his time, Griffith valued the experiences and insights patients had of their condition, and the influence this can have on research:

“I also think Griffith would hope that studies which sensitively capture the individual’s personal experience with alcohol dependence would continue to inform the growing and increasingly sophisticated field of addictions research. As he observed, the alcohol dependence syndrome is a “condition certainly far better described by the average alcoholic than in any book”” Professor Tim Stockwell.

Another key aspect of Griffith’s work was his contribution to Policy. Tom Babor reflects on Griffith as the driving force behind a series of books produced in the 1970’s which sought to align research more effectively with public policy. These books were to inform governments and public health authorities on the best ways to tackle drug and alcohol problems. Dr Babor writes:

“He was clearly the dominant force behind each of these books, without ever being domineering. He had many skills but few personal agendas. He spoke and acted with the natural authority of a born leader. What counted most to him was the ability to share ideas, launch projects and move mountains, preferably by means of evidence-based policy.”

Professor Wayne Hall explores some of Griffith’s less well known work, through his contribution to British cannabis policy in the 1970’s. It was Griffith who argued the case for using clinical research and observation to evaluate the safety of cannabis use, and that lack of reports of adverse effects in the British population did not constitute a lack of harm. Indeed, subsequent research has supported Griffith’s views, particularly around the risks associated with chronic, heavy use.

What is striking from reading through the Supplement, is not only the breadth of the influence of Griffith’s work, but also the number of people, both colleagues and patients, who were deeply touched and inspired by Griffith’s world.

“With Griffith’s shadow set firmly in the background, the people and institutions he influenced now face the challenge of continuing the work of addiction science.” Thomas Babor, John Strang and Robert West.

James Griffith Edwards, psychiatrist and addiction specialist, born 3 October 1928; died 13 September 2012.

For a full list of articles available in the Special Supplement please click HERE.

Joanna Milward, King’s College London

The opinions expressed in this commentary reflect the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the opinions or official positions of the Society for the Study of Addiction.